Account of a good clubbing experience in a small venue

This weekend I went clubbing for the first time in a while, and had a great experience at a small DIY space. I thought it worth sharing my thoughts about what made the event a success, from my perspective as a punter.

Venue MOT is an independent venue in an industrial estate in South Bermondsey, south London. It feels fairly remote, a good 20 minutes walk from New Cross Gate overground station, which actually makes it accessible from home as the Windrush line runs overnight on weekends. The space used to be a car mechanics, hence the name, and the non-residential location presumably defends it from noise complaints. Unusually – something I’ve not seen elsewhere anyway – the venue runs a pair of distinct spaces, each hosting their own separate events each night it’s open. Its a clever move, I think, as cuts costs for security staff (there’s one team at the door covering both venues) and increases the liklihood of the space meeting critical mass of attendees to make running smaller events economically viable.

Some of the things, other than the music, that the night a success for me: A small space, perhaps 150-200 capacity, which on the night had about 80 people in. So plenty of space to dance, not being crammed in like sardines. And intimate enough not to get lost in the crowd or spend forever queing for the bar or loos. Reasonably priced bar with decent non-alcoholic beer and friendly staff. Security staff present but not encroaching on the vibe, didn’t feel like we were under surveillance like some spaces do. Decent sound. Fairly dark with minimal disco lights and not too much strobe to feel constantly blinded. Great to see a welfare worker, clearly a raver, meanerding round the dancefloor to check in on folks, occasionally having a dance too. A nicely mixed crowd, nobody being a creep, and, the best part, everyone heads-down and dancing throughout, nobody constantly on their phone filming or taking selfies (or policing others doing so). Its been noted by many before that queer nights just have a better vibe and the attandees have a better attitude to their night out. Certainly seemed the case here: People were there to dance and that’s what they did.

Of course it helps that the music was great. We were there to see Josh Caffe, who I’d enjoyed at a previous I Love Acid event and Laura had seen at Body Movements. His set was excellent, combining 90s house with loads of 909 drums, acid house squelch and plenty of bits with breakbeats, kind of ravey but still with a house feel. The pacing was great with some really deep, psychedelic stretches. Certain tracks had very dense combinations of loops, building textures and busy repetitions – reminded me of a bit more striated version of Astral Social Club, or Hieroglyphic Being with a slightly more organic sound palette. Support sets from Seb Odyssey (mostly deep house, good gradual build to the others’ sets) and THC (broad range of stuff from 90s house to deep techno, with a bit of half-time stuff at one point) were great too.

Once again, as most times I go to events like this, I was reminded how important DIY spaces are, and how wholesome it can feel to go out all night listening to loud, repetitive music in a darkened room.

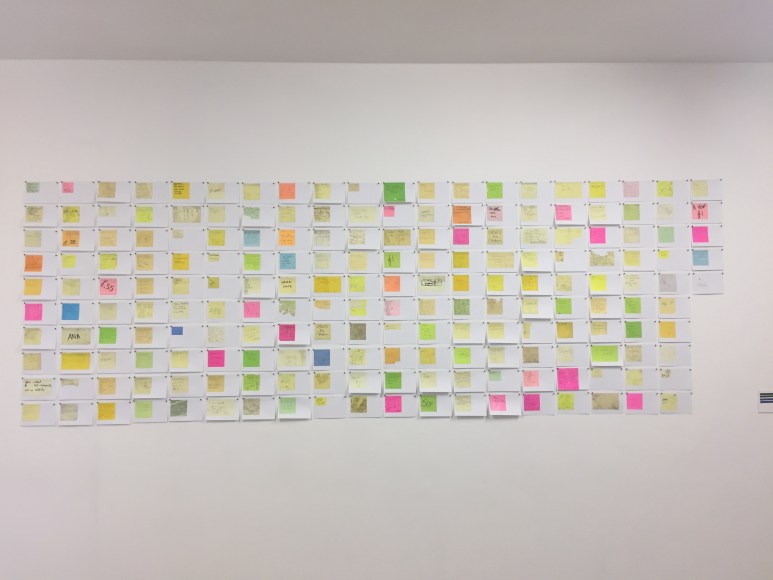

Found Post-it notes in “The Thingness of Stuff” exhibition

The Thingness of Stuff is a new exhibition curated by artist Luke Drozd, opening this Friday 13th February in London, which will include some of my collection of found post-it notes. As discussed the last post about long term projects, I’ve been collecting various things I find in the street for a long time, including playing cards, post-it notes and other bits and bobs. Since 2017 I’ve been mounting the found post-its on card, making them easier to leaf through and examine as a whole collection of specimens. The photo below is from the last time they were exhibited, at my solo show for Le Bon Accueil, Rennes in 2017, which I called the Museum of Peripheral Collections. For Luke’s show, a selection of these will be displayed in the window of the gallery. Details about the exhibition below, and I might write some more about this in the near future.

The Thingness of Stuff

13th – 22nd Feb 2026

Ruby Cruel, 250 Morning Lane, London E9 6RQ

https://www.rubycruel.com/

Opens Friday 13th Feb 6-9pm

Continues 14th & 15th 2-6pm, 21st & 22nd 2-6pm

Or by appointment

The Thingness of Stuff is an exhibition of artists who use collecting as a starting point for making. Curated by artist Luke Drozd, this exhibition looks at the nature of obsession and gathering – via personal collections and archives – and the connections which form between seemingly unconnected “things”.

Paintings composed from record sleeves bought from charity shops, audio work woven together from train announcements, ruminations on the everyday and the overlooked, a spiralling quest to collect second-hand copies of Paul Young’s album No Parlez and more.

As part of the exhibition, a live event called “The Stuffness of Things” will take place on Wednesday 18th February at Multi Storey in Peckham, South London, featuring live sets from Kate Carr and Misery Beacon/Luke Drozd. Environmental Recordings, subtle electronics, and archival noise creates immersive sound worlds and collaged soundscapes.

Artists in the exhibition are:

Kate Carr

Noel Clueit

Blue Curry

Luke Drozd

Alan Dunn

Graham Dunning

Joanne Lee

Mark Pawson

Suren Seneviratne

Maia Urstad

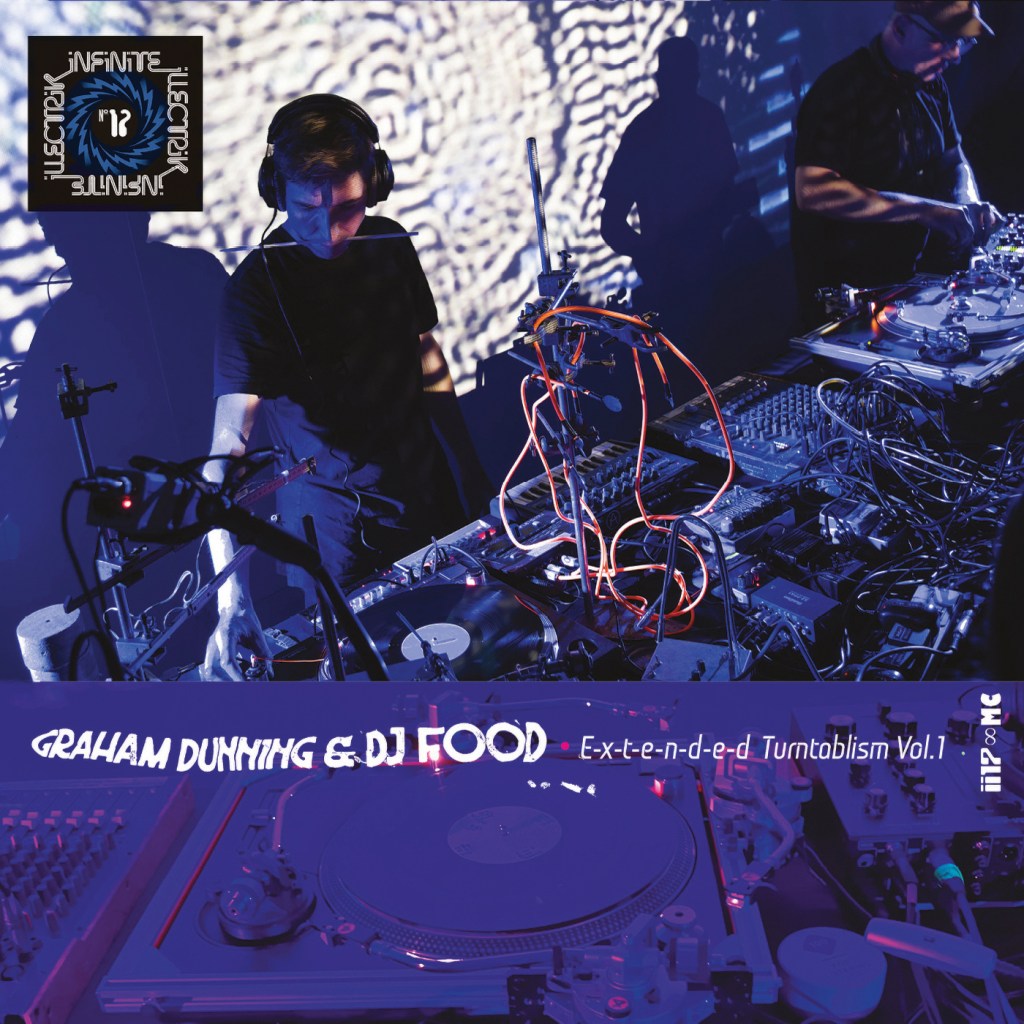

[new release] Graham Dunning & DJ Food: E-x-t-e-n-d-e-d Turntablism Vol.1

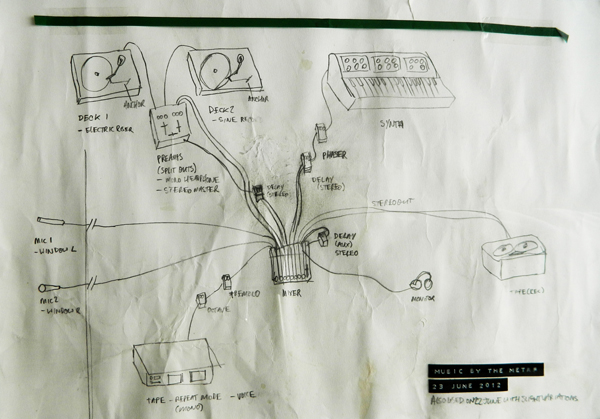

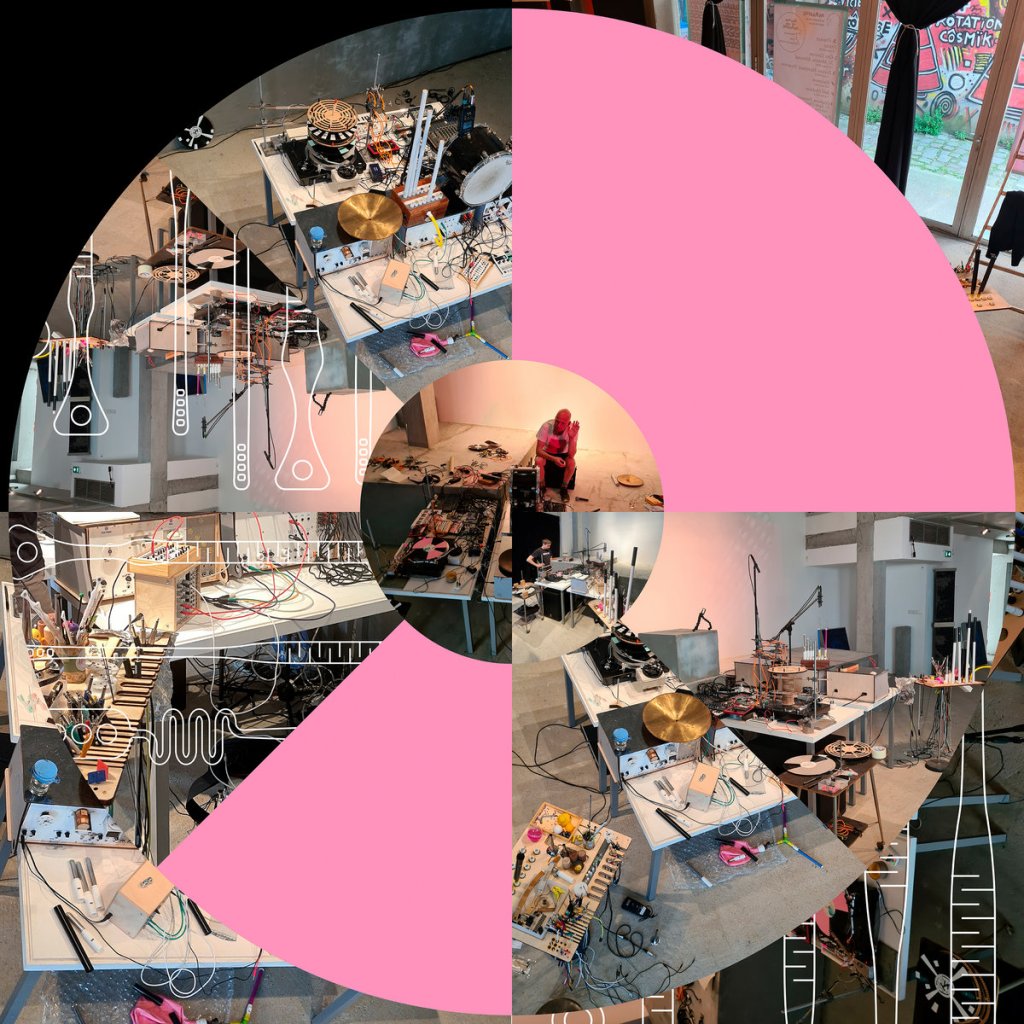

The first gig with Kev was for Robin The Fog’s festival at Iklectik in 2023. Since then we have played a handful of shows, including at a gallery in Bratislava (pictured), a festival in Bedford and an iMax in Bristol. This new tape features edits from that first live show and a bunch of rehearsals in between. I’ve also written about the project in my PhD, which I hope to be able to share soon. Kev’s design for the tape is amazing, and includes some of the visuals from PuttyRubber and Chromatouch, and photos by Keith de Mendonca, Mark Van der Vord, Peter Williams, Mike Letchford, w.ith.lasers and Jason B.

Grab a coyp here: https://grahamdunningdjfood.bandcamp.com/album/e-x-t-e-n-d-e-d-turntablism-vol-1

An improvised rhythmical collage of sound and samples from two e-x-t-e-n-d-e-d turntables. First billed as a ‘modified turntablism soundclash’ the collaboration was conceived somewhat like a back-to-back dance music DJ set, but with two modified turntable systems rather than a standard DJ setup. Graham uses his Mechanical Techno contraption, a tower of modified records and mechanical triggers. DJ Food uses his Quadraphon four-armed turntable with locked groove records.

Graham Dunning is a musician, instrument designer and artist working with sound. His work explores sound as texture, timbre and something tactile, drawing on bedroom production, tinkering and recycling found objects.

grahamdunning.com

DJ Food has been working with turntables for 40 years. His custom-made four-armed Quadraphon deck enables him to bridge the gap between live improvisation and a club DJ set.

http://www.djfood.org

Releases Friday 6th February

73 min cassette tape with 8 page fold out mini-zine insert – only 50 copies.

+ download

https://grahamdunningdjfood.bandcamp.com/album/e-x-t-e-n-d-e-d-turntablism-vol-1

Long Term Projects

Some projects run for a long time. Mechanical Techno has definitely been the one I’ve worked on most since beginning it back in 2014 (here’s a timeline). I’ve been collecting found objects most of my life (as discussed in the last post), though I didn’t really think of it as a creative project for a lot of that time. There are different types of long term projects, I think, and I’ve been pondering this recently.

Andrew Hickey’s excellent podcast series, A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs, is a good example of an ambitious project built from the start as a long termer. Each episode discusses just one track, but this often means giving a whole biographical history of the artist or group and typically loads of social and cultural contextual information too. As an example, the excellent discussion of The Velvet Underground’s White Light /White Heat also requires a potted history of John Cage’s work, the birth of American minimalist composition, and Andy Warhol’s Factory. From the first episode the format was set and, indeed the duration: At an average of an episode per week the whole thing should be done in ten years. I’m impressed by Andrew’s big plans and his dedication to the project.

Another ten-year project I came across recently is an in-depth commentated playthrough of the open-world video game Fall Out 4, by The Skooled Zone. Again, the dedication is impressive. Each episode usually revolves round an in-game quest, or part thereof, with Paul dropping bits of interesting trivia, historical facts and vocabulary, as well as gameplay tips. As a fan of the game it’s cosy and compelling watching: I’m about 25 episodes in (there are surprisingly only 72 in the whole series) and I expect I’ll see it through. Whether Paul expected the run to last so long is not clear. He certainly started shortly after the game’s release in 2015.

When I began working on Mechanical Techno, it grew out of some other existing projects, rather than coming to me as an idea fully formed. I’d already been doing stuff with turntables for years, playing with electronic triggers from drums and other sources, assembling record players and loops to form self-playing music machines, and making dub mixdowns of the output of the assemblages. Mechanical Techno felt like a natural progression to what I was already doing, rather than the start of something totally new. I also had no idea I’d still be gigging, recording and collaborating with it a decade later, and indeed writing a PhD about it. How long the project will continue I don’t really know. Just as I never really planned for it to begin, I have no plans for it to end. It’s likely it will morph into something new – either an iteration of the same project or something distinct. My current plans are to focus on the machine’s unique effects to make some new kinds of music. Extrapolating from the ‘music that sounds a bit wrong’ I’ve been making, to try to make something more alien and angular. It’s in my head as a direction but, as I’ve often found in the past, what actually comes out at the other end might be completely different.

I’m currently reading Tilman Baumgärtel’s book on the history of the loop, Now and Forever. Apart from kicking myself I hadn’t got round to this during my PhD research (I may still mention it in my corrections) I’m enjoying it and getting a lot from it. Reading more detail about Pierre Schaeffer’s locked groove turntable experiments is fascinating – not only is it very relevant to my own work, particularly considering the turntable’s innate capacity for creating rhythmical loops, but also the clear descriptions of the processes from Schaeffer’s diary are really illuminating. And it’s a perfect example of the kind of self-perpetuating long-term project I’m thinking of. Beginning with experiments almost for their own sake, Schaeffer explored the materials, functions and affordances of the technology and the sounds themselves, following the flows and the signposts and just discovering along the way. Musique Concrète seems like such a well considered and perfectly formed approach and set of concepts that it must have been mapped out in advance, a lifetime’s work. But digging into the the processes at play and Schaefer’s contemporaneous self reflections shows the way in which it grew over time.

One thing I found difficult during the main part of the PhD study was trying to stay on track. When I’m feeling at my most creative I’ll have lots of ideas for kernels of projects or starting off points, often relating to a simple practical experiment, and have a strong urge to follow where they lead. Each has the potential to become a long-term project, though most won’t ever get past the testing phase. Now I’m close to submitting the final version of the thesis I’m looking forward to pulling on some of the threads I left behind.

Collecting a whole deck of cards (by finding them on the street)

Picking things up in the street has been a habit since I was a child. I always had pockets full of nuts and bolts and other interesting bits and bobs I’d collected. When I started compiling sketch books for visual research around 2008/9 a lot of found objects ended up in there, with the occasional playing card. Since 2021 I have been collecting playing cards more deliberately, logging the date and location of discovery. It’s a fun and quite silly project, and I enjoy the ridiculousness of tracking it in a spreadsheet. I’ve just set up a proper page for the project, here, which includes my rules for the game.

Each time I add a card to the collection I take a photo of it too. And I have been posting these on instagram. I’m posting now as I plan to shift this over to my blog instead – makes much more sense to keep the archive in one place on the website. In future I’ll do a quick post here whenever I get a new card – typically it’s every few months, so these posts won’t swamp the feed.

The time in between each finding is quite interesting to me. Estimating at an average of about three months between each allows me to make a guess of how long this process might take. The project is a classic example of the “coupon collector’s problem” as explained really well by this Stand Up Maths video. The problem is that the probability of finding a card that you actually need goes down with each card added to the collection. So, the likelihood of picking up a card only to find it’s a duplicate. Using the maths from Matt’s video I calculated I should have completed the collection in about 25 years. So, when I’m in my mid 60s. This is very much a long-term project.

Collaborators and London venues lists – mostly for me

I’ve updated the links page on the website today with two things: a list of most of the people I have collaborated with (and, in some cases, continue to work with) and a list of local venues I often go to.

As I move away from commercial social media, I’m trying to find ways to keep connections and networks visible and viable. The site doesn’t have a “blogroll” as such, but this serves as an alternative: a way to link through to people I’ve worked with and whose work I want to promote. I may add a little more info about each, a few words biography or description perhaps, but also want to try and keep things minimal. I expect I’ll also find this page useful for myself when mentioning people in posts and wanting to link through to their sites.

I put together the venues list for another reason. London is so busy with stuff happening that you have to get used to the sense of FOMO: you can’t see everything you want to, totally spoilt for choice, so have to pick your battles. Occasionally, like today, I find myself with a spare evening and want to find a gig or event to go to. There’s no centralised place for listings now – where I might once have browsed a paper copy of Time Out or, later, searched on facebook, I now find myself clicking through loads of individual venues’ and promoters’ listings to find events. Which is fine. The centralised platforms inevitably fill up with spam, rubbish you’ve no interest in, or miss out most underground stuff which doesn’t engage with it. This list of links is really for me to be able to find stuff quickly. I’ll endeavour to keep it updated. It may also be useful to point out-of-town visiting friends to when they’re looking for something (mainly why I included the location info on the venues list).

The intention of both lists is to be useful as a resource, mainly for myself but perhaps for one or two others too.

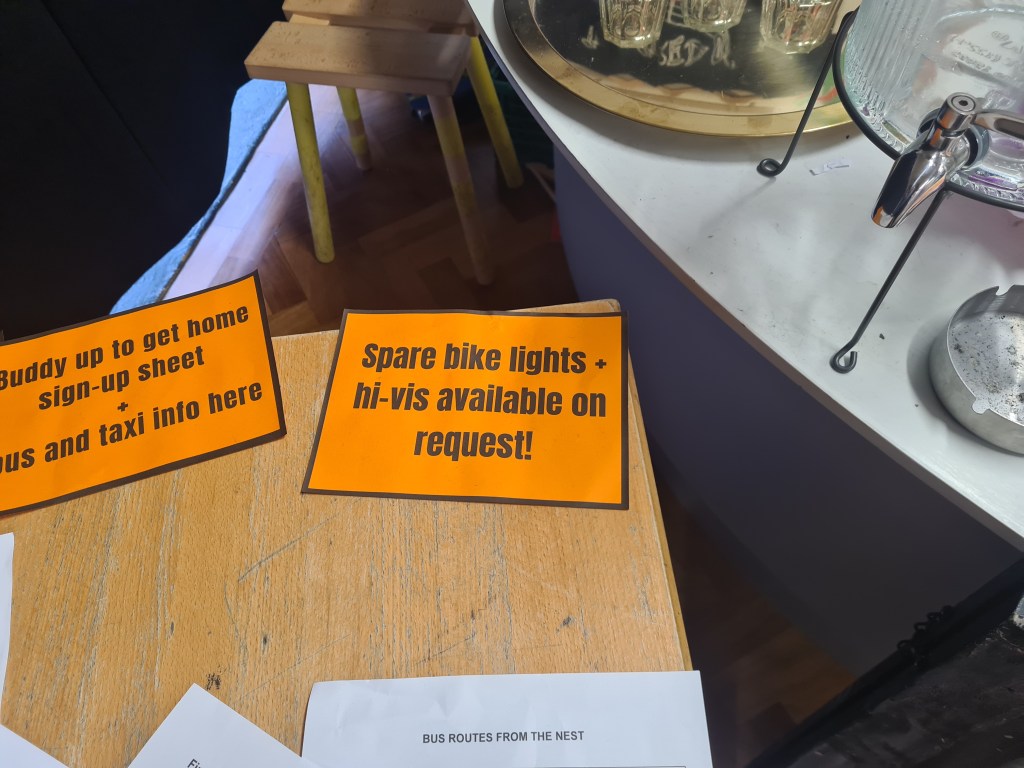

A new home for the Mammoth Beat Organ

This weekend I visited The Nest in Oxford, which is the new home for the Mammoth Beat Organ, to show the custodians the ropes and make some mechanical noises. The Nest is a “wholly inclusive space for young people wanting to express themselves through music,” based centrally in Oxford in a formerly empty shop space and ran by YWMP. Since getting set up in the space in mid-2025 they’ve hosted over 30 gigs, plus weekly hangouts, various courses and recording sessions. They have an active Safer Spaces policy to encourage accessibility and engagement from people who are underrepresented in music, and evidence of this can be seen in the space, including very visible safety protocols and things like free bike light and hi-vis hire and lift-sharing so people can get home safely.

The Mammoth Beat Organ is a big mechanical musical instrument, it takes up a lot of space. It was formerly kept in Sam Underwood’s workshop where we built it together. Sam and Beck have recently sold their house and alll their belogings to travel the world by bicycle – you can follow their progress at bimblingbybike.com – so the MBO became homeless. YWMP are kindly looking after it, with the plan to get some young people using it to make beats, drones and scraping noises – exploring the world of experimental mechanical music.

Me and two of the staff at The Nest started the day building the MBO. Though it’s big it’s designed to be somewhat portable, and various parts can be dismantled. Having assembled the parts and got everything in position we started the motor and everything was working fine. The drum module is possibly the most complex, with different gearing for different time signitures, a variety of cams in divisions of 4/8/16, 8 / 7 / 5 etc., and a load of different beaters to choose from. The air sequencer module has its own ideosyncracies too, and needs to be connected to the bellows (or a big pink balloon) in order to play. Swapping round organ pipes is a nice way to create variation in patterns, and as an unusual way of interacting with a sequencer is perhaps not the most intuitive way to play an instrument. The various noise makers – tombola, drone drum, rotating bin – on the utility module all required their own explanations. And finally the bass banjo with various different pluckers, hurdy-gurdy wheels and dampners.

I’ve got a few video clips to share which I’ll post here once I have time to edit them together. Hopefully the Nest crew will keep me updated with any future MBO activities, which I’ll share here too.

If I was going to write an end-of-year list, this would be it

Typically I enjoy logging things and keeping records. I track what films I’ve watched with Letterboxd. I have list of what fiction I’ve read, which I started in January 2022 in a notebook and recently switched to a spreadsheet. I track my running and climbing too. I find the accumulation of this kind of information satisfying in itself, but it also serves other purposes. For films I’ve watched, it’s a very practical thing. My memory is really not what it used to be and the list serves to remind me what I’ve actually seen. I’m working through the classic 40s and 50s film noirs, for example, and they do tend to blend into one. I’ll often refer to the list in in-person conversations if the topic of films comes up. Tracking fiction is similar, though I do tend to remember what I’ve read more readily than what I’ve watched. I sometimes refer to the list when I’m buying a new book to read, reminding myself about authors or series I’ve enjoyed. Or giving me a nudge to switch genres if I’m in a run of sci-fi. Tracking exercise is quite practical. My monthly climbing wall membership only makes sense if I go at least six times a month, so I started it to monitor that. Logging my running distance is a good motivator – I’m aiming to run one mega-meter (1000km) this year, and currently just need to get another 64km done in the next two weeks.

I have tried logging my music listening in the past, but found it wasn’t for me. My first encounter with algorithmic recommendations was via Last FM, a website which tracked your listening stats and compared this to other members. They invented the verb to “scrobble” for this, so new did they consider the concept. Scrobbling could be done via the website itself, which allowed for artists to upload their discography for streaming (feeling a bit like MySpace from an artist perspective, as I recall. Checking now seems like my artist profile is still there, though I’ve not thought to look at it for years now). Or via a plugin for your favourite media player. VLC player still has inbuilt settings to log your plays. I got quite into Last FM and scrobbling, and enjoyed seeing my stats. Some familiar issues occurred, like hour-long tracks counting as one play comparable in the numbers to listening to a two-minute song. I remember the recommendation algorithm being pretty good but fairly rudimentary, and not always useful in finding new artists. For example, anything rock-based would always generate the Beatles, Radiohead and Bowie in the top artists, however obscure the origin, just by the sheer weight of numbers those major artists would draw. But the reason I finally stopped was when I noticed my listening behaviour being affected by scrobbling. Putting a record on to listen to I hesitated because I realised it wouldn’t get added to my stats. I considered finding the mp3s and listening to the same album that way instead. With that I decided I needed to pull away from the scrobble.

I’ve listened to a couple of interviews with Liz Pelly this year, who has extensively researched the way Spotify works for her book Mood Machine (she was on No Tags podcast back in February and more recently Politics Theory Other), and find it fascinating the way in which the streaming platform has changed the way people listen. I’m not a playlist listener myself, preferring either complete albums (to get a feel of the artist’s bigger body of work) or DJ mixes (to feel how different tunes fit together in a considered way). My brief trial of Spotify ended quite briefly when it didn’t have anything by Om on there, and when the only version of a Joy Division album was a recent remaster which sounded completely different than the original. I understand the ubiquity of the platform but it wasn’t for me. Spotify focuses on the individual listener rather than the genre, scene or artist, tailoring playlists and recommendations to the listener’s sense of self rather than their connection with others. And the end-of-year stats it provides are part of that. I recoil slightly every time someone posts their Spotify Wrapped list – it doesn’t feel to me like a celebration of the music or a contribution to the community, it’s a celebration of their individual taste and a presentation of their personality.

I think the other factor that puts me off the Wrapped-style year-end review is the focus on the importance of the numbers. To a large degree I’m more interested in what’s new than revisiting music. I’m lucky that I get to put together a monthly radio show which gives me the impetus to go looking for new underground and experimental music. I can play anything I like on the show – there’s no pressure or direction whatsoever from the station – but I have some self-imposed guidelines that affect what I play. I try not to ever repeat tracks from show to show. I won’t usually play more than one track by the same artist in a show. And I try and find new artists to play as much as I can, avoiding over-playing the same people. This isn’t something I currently track, though I do have a spreadsheet for this, it’s jut not been updated for a couple of years. If I were to analyse the numbers for the listening that goes into making the show, there wouldn’t be clear trends with tracks or artists moving to the top of the list. Some of these I might only listen to a couple of times. Or it might take me a few listens to an album before I realise I’m not into it, potentially generating bigger numbers that don’t map onto my enjoyment of the work.

This blog post is inspired by a post on mastodon by C. Reider, describing their listening habits as somewhat incompatible with the concept of the year-end list. “i’m constantly listening to music that’s new to me, but not necessarily a lot of music that was released in the last 12 months. might make a big recommendation list of things i liked this year, but 90% of it will be not brand new.”

My own listening is somewhat similar. I don’t think I will make any formal recommendations, however, I kind of think the radio show is how I do that throughout the year (the tracklist for each show is on the blog and I think the bandcamp library page does a good job of showing most of what I’ve bought, despite the issues with it being a closed system).

I mostly listen to DJ mixes when I’m out running. This year I enjoyed digging into the archives of Field Maneuvers festival, with favourites from Jay Duncan, Ben Simms and Local Group. I also really like the live mixes posted by south London record shop Planet Wax on youtube, and highlights were by Louise Plus One and Jerome Hill. In terms of bigger numbers, the stuff I end up listening to often is also context dependent. I’m excited to be going to see Pharaoh Overlord live for the first time next year, so have been going back over their stuff and checking newer releases on their bandcamp page. Because I’m moving house soon I’ve been looking through my CDs and records, listening to some albums I’m less familiar with, which is one of the benefits of physical media. Similar to what C. Reider said, not everything I listen to is newly released, but often it’s new to me. All this is to say, I’m not writing an end-of-year list, but if I was, this would have been it.

What am I going to do after my PhD?

Having passed my viva with minor corrections this week, my PhD is pretty much in the bag (wahey!). I’m looking forward to sharing Mechanical Techno: Extended turntable as live assemblage with the world once I’ve made the last few changes. In the meantime, I shared the documentation of my show in Sheffield last year which forms the basis of chapter 4 of the thesis. You can watch it here.

Working on the write-up has taken most of 2025, and I’ve put off a lot of things I wanted to do in that time in order to get it written. No complaints, that was the job I needed to do, but I’m now looking forward to spending time doing some more fun stuff again. As such, after my viva I bought the new Dungeons & Dragons boxed set, which I’ll be running with some friends from January. And a load of sci-fi and hard-boiled detective fiction to read. Three events coincide this coming weekend and I hope to attend all three. Iklectik’s annual NOISEMAS celebration is a twelve hour show with back-to-back noise sets, featuring a lot of friends performing and no doubt many others in the audience. The last BRAK of the year, a regular free improv show where Cath Roberts, Colin Webster and Tom Ward each pair up in a new duo. Always a lovely meet-up with an overlapping group of folks. And Das Booty, a rave with DJs typically playing stuff from the harder and weirder end of techno, breaks, UKG and bass music – hoping to convince some of the noise crew to come along after.

Whilst I’ve been fully immersed in music making and thinking about music recently, I’ve missed going out to gigs as often as I normally would, and haven’t been playing much at all this year. The majority of my social life usually revolves around events like these and a main plan for me going forward is to get more involved again. That also means resurrecting the tape label Fractal Meat Cuts, and I’ve got a few exciting things in the pipeline for that. Generally my plan is also just making more stuff (music, instruments, other things), sharing what I’m doing and trying to connect more with people and the scene.

One change I plan to make in 2026 is coming off instagram, which has been on the cards for a while. My main concern has been losing connections with people, being less able to share what I’m doing and finding out what others are doing. I don’t want to go into all the reasons for disconnecting from corporate social media here, perhaps that will make another blog post, but I really want to try and see if it’s possible to do things in a different way. I find way these platforms shape the users (both contributors and consumers) quite insidious. My main plan is to try to make my online output sustainable (for me to do it without feeling under pressure to do so), accessible in the long term, formatted on my own terns and not to suit the algorithm, and fun to make and engage with. I also want to be able to build and sustain networks with people. In practical terms this is going to look like: more regular blog posts, starting the monthly email list again, staying engaged with Mastodon (loving the community already there), and collating video documentation on youtube (rather than just short clips on insta).

Consider this post, then, the first of many.

2 new compilation tracks, and 2025 releases round-up

I’ve got two new tracks out today, and thought this would be a good opportunity to round off my year’s recorded music outputs too. Today, Friday 5th December 2025 is the last “bandcamp Friday” of the year, where anything you spend on the site goes directly to the labels/bands without bandcamp taking a fee. I have two tunes out today on two different compilations.

Compassion through algorithms volume III is a digital compilation of tracks mostly by live coders, to generate funds for charities working in Palestine. My contribution is an edit of a Mechanical Techno studio jam. There are over 50 tracks on the comp running all sorts of electronic music genres, including techno, electro, breakcore, drone and noise. Priced at £1 or more, with buyers encouraged to donate whatever they can, all proceeds are donated equally between Medical Aid for Palestinians (MAP), working for the health and dignity of Palestinians living under occupation and as refugees [www.map.org.uk] and A M Qattan Foundation, supporting culture and arts in resisting systematic erasure of the Palestinian people [qattanfoundation.org].

Collapsing Tape: Experiments in Rupture and Repair is a compilation on cassette and download by Bristol based label Collapsing Drums. My track on here is from the duo with Sam Underwood, where we combined my extended turntable with Sam’s acoustic modular system to create some clattering and wonky rhythmic electroacoustic music. The piece is an edit from our performance at LineUp! Festival in Malvern last year, which also features in chapter 6 of my PhD. The design of the tape is lovely and the rest of the tracks are great too, including some of my favourite noisemakers like Mariam Rezaei, Valentina Magaletti, Sculpture and Mr AKA Amazing.

I had two other releases earlier in the year too which are both available online. Some recordings from the RMA Study Group, Music and/as Process were released by the label associated with Birmingham Conservatoire, where the conference took place in 2024. Unusually for a multi-day academic event, us attendees were encouraged to bring instruments along, and the paper presentations were interspersed with both performances and opportunities for us to make music together. This album collates some of those sessions, including “directed improvisations led by Alistair Zaldua, whose ensemble line-ups were chosen at random, allowing for a fresh and dynamic approach to music-making. The album also features performances of contemporary works: Critical Mass (2023) by Steve Gisby, Post-card Sized Pieces (2020) by Sophie Stone, and What Is Left If We Aren’t The World (2021/22) by Emmanuelle Waeckerlé.” The album came out in June 2025, and you can download it here.

I worked with longstanding collaborator Sascha Brosamer on a new pair of recordings in late 2022, when we toured together and did some recording at my uni. Telescope/Microscope was released on Total Silence, Sascha’s label for new music and conceptual art, in August 2025. One of the pieces is expansive, cosmic and psychedelic, featuring extensive use of guitar, synths, and textural sounds. The other is more introspective and focused on phonomanipulation, noise and a monochromatic, minimal palate. Both use lots of turntable (me) and gramophone (Sascha) and many discs from our respective collections of field recordings, machine noise and other unusual documentary sound. You can download the album here. We have some exciting stuff in the pipeline, with our work featuring in a documentary about architectural history, and a performance for the gallery debut of that work in Berlin in 2026.

Finally it’s the anniversary of the release of Beaux Timbres, the album me and Sam Underwood released last year with Accidental Editions. This also features in the PhD, and it’s been great going back over the project to write about it over the last few months. The label still has copies of the vinyl and special edition modified record, as well as the download. All available here.

Lots more to come in 2026. I’m also planning to post here more as I’ll stop using instagram and need some way to promote what I’ve been doing! Stay tuned.