clacky keyboard

Spending more time writing recently – journalling, blogging and writing some articles and papers – I’d become a bit frustrated with my cheap, light-touch bluetooth keyboard. I felt like I needed something chunkier and more tactile, slightly more responsive and nicer to use. My second critera was price: I got this one for about £30. Finally I wanted to have separate number pad keys, so didn’t want anything too compact. In part I wanted to be able to play Caves of Qud properly again at some point, and in part for nostalgia for when I used to use an external num-pad for selecting patterns on Fruity Loops for live sets.

I like the colour sheme – off-white, dark grey and orange – and coincidentally it matches various other things on my desk, including stationery and the book I’m currently reading. It also reminds me of a Roland TR-707, one of my favourite drum machines. In fact, the 707 is the only model from the range I’ve actually had a play with, and its chunkiness, and plasticky feel is a bit smilar to this keyboard too.

Though it wasn’t a factor in choosing a new keyboard, the sounds it makes have taken a bit of getting used to. The soft-touch keyboard was almost silent, and this one is very clacky indeed. I was immediately reminded of the Mechanical Keyboard Sounds album released by Trunk Records a few years back. Somewhere between a novelty record, an archival document and an ASMR collection, the tracks feature typing on various retro and modern setups, with different degrees of lubrication and modding. The mechanical keyboard scene is a rabbit hole I can’t afford to be drawn into, either in terms of money or time, but I’m now accutely aware of some upgrades I could make to the way my tying sounds.

Science fictions and self reliance

This afternoon I’m joining a zoom call with some first year graphic design students at Sheffield Hallam – they’re to be tasked with making a video in response to some of my music, “using experimental video, typography and use After Effects to blend videos (for the first time).” I wrote the following to see if these might be fun jumping-off points for their projects.

There are two fictional narratives I have applied to my work. First, the escaped clanking replicator; second, the post-apocalyptic music machine.

One facet of Mechanical Techno is that of recycling existing and unwanted music. The records I use, either to sample from or to create trigger records, are white labels rescued from bargain bins and junk shops. Artefacts that may once have had cultural and monetary value but which have found themselves dispossessed, thrown away as worthless1. Mechanical Techno recycles the physical objects and recycles the sounds stamped into them. The output is new music, and indeed new records. The machine eats old music and records and spits out new ones.

The ‘grey goo scenario’ describes the following hypothetical apocalyptic situation: Nanobots are in common use for various tasks including building and repairing technology. By their nature, large amounts of these devices are necessary. As such, an efficient way to maintain sufficient quantities of nanobots is to have them capable of reproducing: robots which can build more robots. In the grey goo scenario, these nanobots run out of control, converting all available matter into more and more nanobots, an exponentially accelerating snowball effect which eventually turns all the molecules in the universe into grey nanobot goo. Zooming out from the microscopic scale, a replicating machine could be imagined which would build clones of itself. The ‘escaped clanking replicator’ is a large machine-producing machine run amok, like a giant version of one of the nanobots in the grey goo scenario2. If the Mechanical Techno machine continues to run indefinitely, perhaps it will eventually produce so much music and so many records that no others exist in the universe.

The second science fiction trope I’ve considered in relation to my work has been to think about music making post-apocalypse. In the Fallout video game franchise, much technology is salvageable from the past. Armour, weapons and ammunition can be cobbled together from leftover scrap. The results don’t look elegant or work very effectively, but they get the job done. In the post-apocalyptic wasteland depicted in the TV show Station Eleven, smartphones and computers have long been rendered useless, relegated to the status of museum exhibits. Even with the possibility of generating electricity, these devices are too complex and too reliant on external networks to have any practical use.

Whilst initially made using hardware drum machines, synthesizers and samplers, nowadays the majority of electronic music is created ‘in the box’. A program like Ableton Live can be used to generate sequences, sounds, effects and automation. Software provides emulations of classic drum machines, tape recorders, effects units, orchestras, and other technologies. Increasingly software follows a subscription model and requires authentication of purchase over an internet connection.

Mechanical Techno isn’t the usual way to make electronic music. Some of the sound sources come from commercially available synths and effects pedals. But much of it is generated from handmade devices, hacked and modified objects and repurposed vinyl records. The process is clumsy and the resulting music sometimes sounds a bit wrong, but it gets the job done. As such, Mechanical Techno could be imagined as a future-proof, post-apocalyptic music. It isn’t reliant on computers, on a software subscription, or on an internet connection.

- As Kyle Devine writes in Decomposed: The Political Ecology of Music (p119), ‘Plastics perish. In addition to the challenges and hazards of producing polymer compounds, and in addition to the social inequalities and environmental infractions of record pressing facilities, plastic recordings that reach consumers eventually wear out, or become individually unwanted, culturally unfashionable, or technologically obsolete. Disposal and dispossession are the versos of newness and possession.’ ↩︎

- Both of these are paraphrased from two Wikipedia pages, Grey Goo and Self-Replicating Machine. ↩︎

Five ways of using contact mics

Following on from the recent post about DIY turntable styluses, here are some other uses for contact mics. When I used to teach the Experimental Sound Art evening class I made four suggestions for ways to use contact mics: amplifying small objects, amplifying large objects, amplified surface (scraping table), and making an ‘instrument’. These are covered below, but I’m glad now to add ‘DIY stylus’ as a fifth category.

A good approach I’ve found for contact mic explorations is to use some sort of portable amplification and headphones, so you can monitor what sounds you’re getting in real time. Handheld recorders (like those made by Zoom or Tascam) are good for this as they have easy to use inputs. I used to use a Zoom H4 and have two contact mics attached, then listen on headphones, choosing later whether to use the channels individually or in stereo. One thing to bear in mind is that piezo transducers can output quite loud sounds as well as more subtle ones. Handling noise in particular can be quite harsh – sticking the contact mics down, accidentally knocking them, etc. So I recommend taking the headphones off whilst adjusting the position and gradually bringing the volume up to a level where you can hear what’s going on.

There are plenty of ways to attach contact mics but the main thing to remember is in the name – contact. The disk needs to be secured in such a way that the vibration of the object can pass into the metal of the disk. I often use electrical tape, as it’s not too messy when you peel it off, though it’s also not particularly secure. For permanent attachment it’s possible to drill through and bolt contact mics (thanks Sam Underwood for that tip), or I’ll sometimes use two part epoxy glue (like araldite) if it’s attaching to something hard and not too bendy. This could probably be a whole post on its own, so I’ll keep it brief.

I’m not going to cover making contact mics here, or talk about impedance and pre-amp options, but might do a separate post about these topics further down the line. A great resource on all of this is Nicolas Collins’ Handmade Music: The Art of Hardware Hacking, which I would recommend to anyone interested.

1. Stylus and scraping implement

Over on Instagram, Michael Cella made a great stylus with a 3D printed housing, playable by hand on records and other surfaces. The stylus end was essentially a pin attached to a contact mic, housed in a chunky wand (It reminded me of the Magic Pencil from British kids’ TV show Words and Pictures). Having the holdable part isolated from the pickup is great to avoid handling noise and the potential buzz/hum that can occur when physically touching the metal parts of the piezo disk.

Pretty much anything can be used as the ‘needle’ part of the stylus. Just stick something onto it, and find some things to scrape it on. Some examples might be: cocktail stick, bamboo skewer, knitting needle, drinking straw, biro, stick, jam jar lid, clothes peg, shard of glass… In one workshop I led, a participant sellotaped a ping-pong ball to a contact mic, then spent the entire session with headphones on scraping it along the walls of the room, and every surface they could find. The ‘stylus’ material makes a huge difference to the sound, as does the choice of surfaces you ‘read’ with it.

The size of the stylus is potentially interesting to explore too. I’ve done a couple of projects with amplified sticks and other materials, scraping them along the floor, tracing out spaces for their sonic textures. Field Tracing (2017) maps a terrain in the Black Forest using four different materials, the recordings and videos played simultaneously in an installation along with the styluses themselves. For A Tracing of a Single Tide I walked the length of the beach at Walton-on-the-Naze with a stylus made from driftwood.

2. Amplifying small objects

Possibly the most obvious way to use a contact mic is to amplify the small sounds you can make with a single individual object. It’s fun just to try lots of things out, and for workshops I had a collection of both prosaic and unusual items for people to explore (charity shops are a great resource, as is the pound shop). Off the top of my head some favourites were: pie tray, comb, ladle, slinky spring, pine cone, egg slicer, toy cymbal…

The way you attach the contact mic can make a big difference to the sound. It’s important that the ‘contact’ is good, but also that the object is free to vibrate – so it’s a fine balance. Too much sellotape and your teaspoon will no longer ring when you flick it. Too little and the piezo will fall straight off. It also makes a difference where you hold the object, and how you activate it. Sometimes dangling the item by the wire of the contact mic works well, to let the whole unit vibrate freely. Flicking, brushing, scraping, bouncing, blowing, swinging, twisting, bowing or bending an object may or may not reveal some hidden sound – the joy is in finding out.

Working with metal objects is sometimes tricky, as they can short the connections on the contact mic leading to the sound dropping out (this isn’t dangerous, as there is very little current in the audio circuit). The area to avoid is the side of the disk with the white circle – if an electrical connection is made between here and the edge of the brass disk, the sound will stop. One workaround is to cover the back of the disk with electrical tape to insulate it. It’s also possible (though a bit tricky) to stretch a balloon over a contact mic. Be aware though that any additional dampening will also potentially muffle or change the sound you get – again it’s a process of testing it out. This came up in a workshop with someone pressing a contact mic into a ball of wire wool – it sounded lovely and crunchy but intermittently cut out. We got around it with the balloon technique.

Adam Bohman uses contact mics on small objects to great effect. In improvised performance he uses a table crowded with wine glasses, springs, pieces of polystyrene, clothes pegs and other (carefully selected) tat, and plays these with violin bows, files and other activators. In order to avoid having to mic-up every item individually, he uses clip-on contact mics, and has volume pedals at his feet to mute the signals as he changes mic positions.

3. Amplifying large objects

Larger objects are fun to amplify too. Examples might be bins, fire extinguishers, windows, railings, ladders, a playground slide, a bicycle wheel, a radiator, a sculpture… Again placement and attachment will give varying results and it’s usually best to try a few positions before committing. Here a stereo pair of contact mics can give great results. I once recorded a bottle bank with two contact mics and my zoom recorder, then did the recycling: it sounded uncannily like being inside the bin. It’s worth bearing in mind that attaching wires to large objects in public places might look strange or even suspicious to some people. I’ve never had any issues, or even been approached, but it’s often been in the back of my mind.

Again there are different approaches to ‘playing’ the large object once it has been amplified. Drumming, scraping, flicking, etc all work – and the choice of beater or activator, and where you strike it, can make a big difference. Placing contact mics on a window can sometimes pick up sounds from outside, but they will be ‘filtered’ by the material properties of the glass itself – in practice this means traffic rumble is heard more than, say, bird song. Rain or hail directly hitting the glass would produce great results. Artist Melanie Clifford has worked extensively with amplified panes of glass, often amplifying barely audible high frequency resonances for use in her video work.

4. Scraping table / amplified surface

Almost the exact inverse of the stylus – what if we amplified the record instead?

To make a scraping table involves amplifying the surface and then using it to amplify other objects interacting with it. Again, a pair of contact mics can be used and the resulting recordings can be used to make interesting stereo interactions. The choice of surface is important: a resonant table works well, a dull and deadened table less so. Once a surface is miked up, try: spinning coins, rolling marbles, scattering rice, pouring water, releasing small creatures…

One of my favourite recordings, which I still use often in performances, is the shelf inside a pigeon shed with a pair of contact mics: scrabbling claws dominate, but the pigeons’ cooing comes through surprisingly clearly too (presumably in part through vibrations down their legs). I’ve also made an amplified surface from an old snare drum skin, and a video of playing some objects with it: here. Other things that work well as surfaces are vinyl or shellac records, cymbals, baking trays, corrugated cardboard, the lid off a turntable, plastic chairs.. Again, the material properties of the surface make a big difference, so it’s good to experiment.

Lee Patterson has used contact mics in lots of innovative ways, one of which is a metal plate he uses for amplifying springs and perfume bottles. The plate itself is suspended on springs to isolate it from external vibration which might cause feedback. The resonance of the plate interacts with the springs he attaches to its edge, creating a complex and responsive system capable of a vast range of sounds from very minimal and subtle movements.

5. An “instrument”

Though it can seem quite a daunting prospect, it’s possible to build an instrument of sorts by combining different objects with an amplified surface or box. Baking tins, jewellery boxes, tupperware, drawers etc can work nicely. Once the box is amplified, anything attached to it can be used as a sound source. Elastic bands stretched across make almost-convincing guitar and double-bass sounds. Screws, nails, nuts and bolts can be attached. Anything that twangs or can be plucked works well – springs, cocktail sticks, rulers, brush bristles, hairbands… Choice of plucker / beater/ scraper matters a lot too, so there are lots of options. Here are a few photos from instruments made during one session of the Sound Art course: [link].

Hugh Davies called this type of instrument a ‘Sho-zyg’ named after a volume from an encyclopaedia he turned into an instrument. Anton Mobin calls his instruments ‘prepared chambers’ and they feature springs, motors, contact mics and speakers – making versatile and playable systems for performance and recording.

A handful of decent music podcasts

Podcasting feels like one of the exciting frontiers of DIYism. Pretty much any topic, niche TV programme, hobby or interest will have a couple of podcasts about it. There’s scope for different levels of professionalism, and different flavours of presentation, from slick radio journalism to bedroom ruminating to chatty conversations. I listen to podcasts a lot, generally when I’m out walking, on public transport or working on something which doesn’t require my full attention. I’ll often fixate on a particular show, binge-listening till I lose interest or find a new one that draws my attention. Not all of the podcasts I listen to are music focused, but here are some of my recent favourites. Check them out ‘wherever you get your podcasts,’ as they say.

A classic format that does what it says on the tin. Musician Huw V Williams chats with a different player (mostly) from the British free improv scene. The interviews tend to be fairly long, usually over an hour, and they’re generally lightly edited conversations, so you really get a feel for people’s approach and attitude towards their work. It’s nice to see a few folks I know on the list, but also great to hear about new players, or put a voice to a name in some instances. There are some short sections of music which give context, something (sometimes missing in music podcasts, doubtless due to copyright / content match issues. There are two aspects I find fascinating in these conversations: the weird and wonderful routes people have taken to get where they are, and detailed discussion of their practical and theoretical approach to improvised music making. A good example is the first episode with saxophonist Dee Byrne – though because the sound quality improves later in the run, be aware this one is a bit rough round the edges.

Hosted by Ràdio Web MACBA in Barcelona (one of several longstanding shows on the institution’s platform), Probes is an in-depth timeline of developments in musical instrument design and technique, covering the history of avant-garde music. Written and presented by musician and author Chris Cutler, it’s full of examples of unusual instruments and their stories. There are loads of audio examples in this show, often several minutes of music at a time, which really helps to contextualise the ideas he’s discussing. Each show is thematically grouped around a specific development or line of enquiry – which Cutler calls ‘probes’. This might be a compositional component (there’s an episode on glissandi), or a specific technique (see prepared piano), or a particular instrument and its extensions.

While the episodes are in-depth, they are firmly focused on western classical music. Though various types of music and instrumentation from the global south do get mentioned, they’re only really qualified as being important probes once their contributions to the western art music tradition can be established. Cutler is aware of this, and does try to be expansive, but at times I found this frustrating. With the discussion of such a large number of instruments, composers and musicians there’s also the potential issue that some information has to be left out. It was intriguing, for example, to hear about Percy Grainger’s utopian ‘free music’ machines, but it was not mentioned that Grainger was a staunch and active white supremecist – an important caveat when considering the impact his ideas may have had on musical development.

Probes feels like a series of lectures rather than a chatty and conversational podcast. As such it requires a different type of listening. I’ve spoken to Sam Underwood, who recommended the podcast to me, about this – needing to go back through episodes and make notes. It’s a great series for broadening understanding of instrument design specifically, something both me and Sam are researching and working with.

A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs

I find the scope and ambition of this project absolutely astounding. Andrew Hickey is planning on releasing an episode of this podcast every week for the next ten years. Each show is meticulously researched and written in full, and presented by Hickey with short excerpts of each of the tracks he mentions. There’s also a mixcloud for each episode featuring all the songs in full. It’s an incredible resource. I’m about 80 episodes into the series so far, of the 187 which have been published. If it keeps to schedule it should finish some time in 2028.

The series begins sometime in the 1930s and there’s an extensive exploration of the roots of rock n roll as a genre – genealogy feeding in from western swing, doo-wop, southern gospel, and a dozen other genres which were new to me or too closely related for me to discern. Hickey discusses developments in music production (tape echo in rockabilly); the introduction of specific rhythms, riffs and arrangements; behind the scenes figures including managers, radio DJs and tour promoters; and unpicks the complex rhizomatic relationships between musicians, bands and labels. Refreshingly, he’s careful about giving context to potentially problematic material, and highlights the racism, misogyny and homophobia so inherent in the industry (and society as a whole) in the decades he’s discussing. Abusive and egotistical rock stars aren’t given a free pass, Hickey clearly identifying the kind of toxic behaviour which more mainstream rock music histories might gloss over.

While the stories are fascinating, personal taste will dictate which parts of the series are more interesting. The biographical information is at points incredibly detailed, to the extent that I might sometimes tune out if it’s an era I’m not particularly invested in. Sam, who also recommended this podcast to me, has come across episodes later in the series that stretch to four hours long. For me this is a podcast to listen to whilst doing other things. Hickey’s delivery is direct and to the point and I find it somewhat meditative and relaxing.

So far I found the first couple of dozen episodes of most interest. The way that a genre’s sound evolves from distinct and overlapping parts. Aspects are emphasised and repeated and become part of the makeup of the genre. Accidents of coincidence, workarounds or financially motivated decisions can steer creative outcomes in unexpected ways. At the best moments, Hickey’s skill in following connections – social, technological, aesthetic, cultural – and detailed: drawing out of the causal relationships creates a compelling and inspiring body of research I keep coming back to.

Switching away from music history, and switching genres again, No Tags is very much about present day electronic music and club culture. Presented by Chal Ravens and Tom Lea, both music journalists who cut their teeth with FACT magazine, their stated intention is to catalogue and archive snapshots of underground music culture that might otherwise go undocumented. Breaking from the hype-cycle focus of much coverage of electronic music, it’s great to hear about scenes and artists that are working away in the background without necessarily feeding the content machine. Most episodes feature an in-depth interview bookended with some chat.

The episodes do feel like interviews rather than the less formal conversations of, for example, the Improvised Music Agenda podcast, with questions probing the guests’ professional and personal histories and how their ethics feed into their work. Community building is a recurrent theme, with guests discussing festival curation, radio mentoring and queer clubbing. The presenters’ passion for both the music and the scenes and connections around it is infectious, and the guests are well chosen to highlight key figures to their particular niches. While the presentation is quite polished and the conversations on the whole quite rigorously journalistic, there are some fun and silly bits too, and when guests aren’t in the studio the chat can turn slightly gossipy, which I like too. Ending on film chat each episode is also a welcome gear change..

I heard of this podcast directly from No Tags, when the interview with New York’s Sorry Records covered some of the city’s clubbing history and particularly the loft party scene. Tim Lawrence is an expert on New York in the 70s and particularly David Mancuso, whose loft parties were hugely influential to both the counterculture and modern club culture. I first came across cohost Jeremy Gilbert through an essay on Deleuze and improvised music1, which is still a text I refer back to often. I’d also read his more recent book Twenty First Century Socialism, and somehow assumed his interests and output had moved away from music and more squarely into writing about politics. So his involvement here was something of a surprise to me.

If podcasts generally sit on a spectrum with conversation at one end and lecture at the other, this is right in the middle, feeling like a very focused panel discussion. It’s very detailed and very in-depth, to the point that it can feel as though it’s covering the same ground sometimes. But the depth of knowledge and the connections the presenters draw are formidable, and really informative as to the roots of modern club culture and indeed electronic music.

Mancuso’s loft parties began as a staged environment for friends to take acid in: colourful decor, organic flowing music (from the atmospheric to the ecstatic), a diverse and eccentric crowd, and a focus on freedom of expression at a time when society was incredibly restrictive, particularly for people of colour and gay people. The podcast explores the social and economic factors that led to the existence of these parties, the practical aspects of how they worked and who was involved, and the knock-on effects across culture and society. The scope is at once broad-reaching and incredibly focused. It’s extremely in-depth and thorough in both its analysis and detail. Music features throughout, though in tantalisingly small doses.

Another aspect I particularly enjoy is the overtly practice-research method of ‘putting your money where your mouth is’: the longstanding loft-party inspired clubnight series ran by the presenters, Beauty and the Beat. Modelled on Mancuso’s loft parties (right down to the audiophile Klipschorn speakers), the events aim to capture the spirit of the loft and allow contemporary audiences to experience something like it. Throughout the podcast the practicalities of running the club are discussed in detail too, and it gives weight to the theory and discussion to know it’s grounded in this way.

- Gilbert, Jeremy (2004). Chapter 6 Becoming-Music: The Rhizomatic Moment of Improvisation. In Ian Buchanan & Marcel Swiboda (eds.), Deleuze and Music. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 118-139. ↩︎

DIY styluses for playing mangled-up records

I was asked recently for some advice about turntable styluses for playing broken and mangled records. Flo from Plattenbau Kru – who use stickers, scratches, cracks and breaks to modify their vinyl – said the ‘project is using up A LOT’, as might be expected. Offering a couple of suggestions led me down a bit of a rabbit hole, thinking about how people use alternatives to standard cartridges and needles to generate different effects.

Flo mentioned John Cage’s cactus stylus, which is something of a legend. In fact I’m not aware of him using it to play back records (though I could be wrong). There is some great footage of Cage playing the cactus as an instrument, and I believe that the amplification is provided via turntable cartridges (as opposed to contact mics as might be expected nowadays). A similar approach – replacing the needle in the cartridge with different material – is used by Andrea Borghi to play stone and marble disks. Borghi uses a piece of wire, with a physical twist and a fork like a snake’s tongue (as pictured on the front page of his website), to enable him to read the rough textures of the different materials, creating crackling and ever-changing textural soundbeds. Certain of his other compositions use close-miked crackling fires and other parallel pointillist sounds. Recently doing the rounds online have been clips of Leonel Vasquez’ Canto Rodado sculptures: rotating stacks of rocks with acoustically amplified scraping styluses, creating multi-pitched drones with some textural clattering. I can’t quite tell whether there’s some digital augmentation to the sound too, the output is so smooth and melodious.

Records can really be used to vibrate or activate any material that’s small enough to fit in the groove and light enough to be moved by it. It’s particularly satisfying to listen to a record acoustically via a paper cup with a pin attached to the bottom of it. Michael Ridge has used a plastic bank note to play sounds acoustically (amongst loads of great noise experiments on his youtube channel). One of my favourite explorations of acoustic activation is by Sseeaan Rroowwee, who uses screwed up balls of paper on a pair of decks, like in this live set. The sharp corners can contact the records at multiple points, generating sound from different parts of the record at the same time. Multiple balls of paper can create an extremely quiet cacophony, many tinny sounds playing concurrently. Physically manipulating the paper changes the contact points and hence the grooves – it’s an incredibly subtle and engaging performance. At the other extreme of multiple, changing points of contact is Evicshen’s stylus glove – fingernails made from styluses which provide a direct and tactile interface with her cast and modified disks.

An invaluable resource for turntable experimentation is the catalogue to the Broken Music exhibition in 1989, edited by Ursula Block and Michael Glasmeier. A quick glance through brought up Laurie Anderson’s turntable violin with stylus bow (a precursor to her perhaps better known tape bow violin); Joseph Beuys’ 1958 Stummes Grammophon (with a bone in place of the tone arm) and 1969/81 untitled gramophone with an amplified sausage attached to the soundbox; and details from pieces by Mauricio Kagel’s works including a dining fork and a sharp metal finger attachment being used to play records.

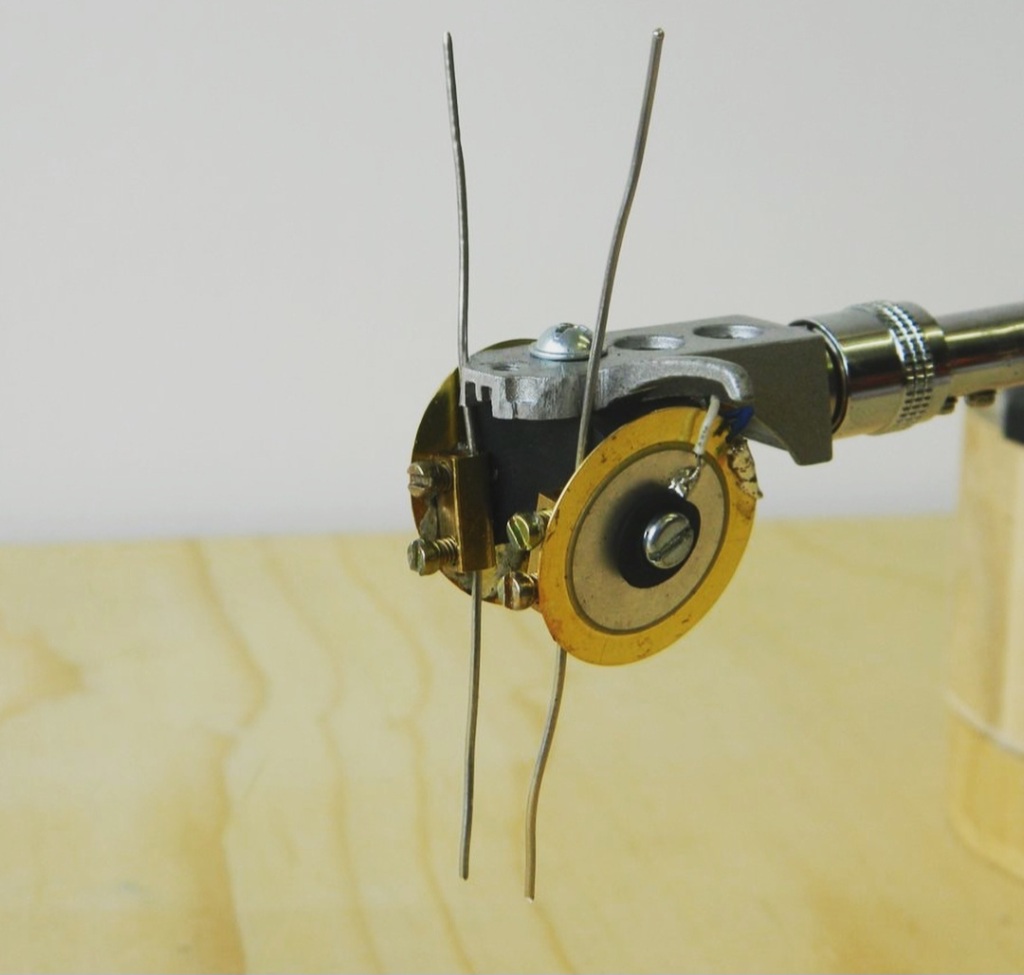

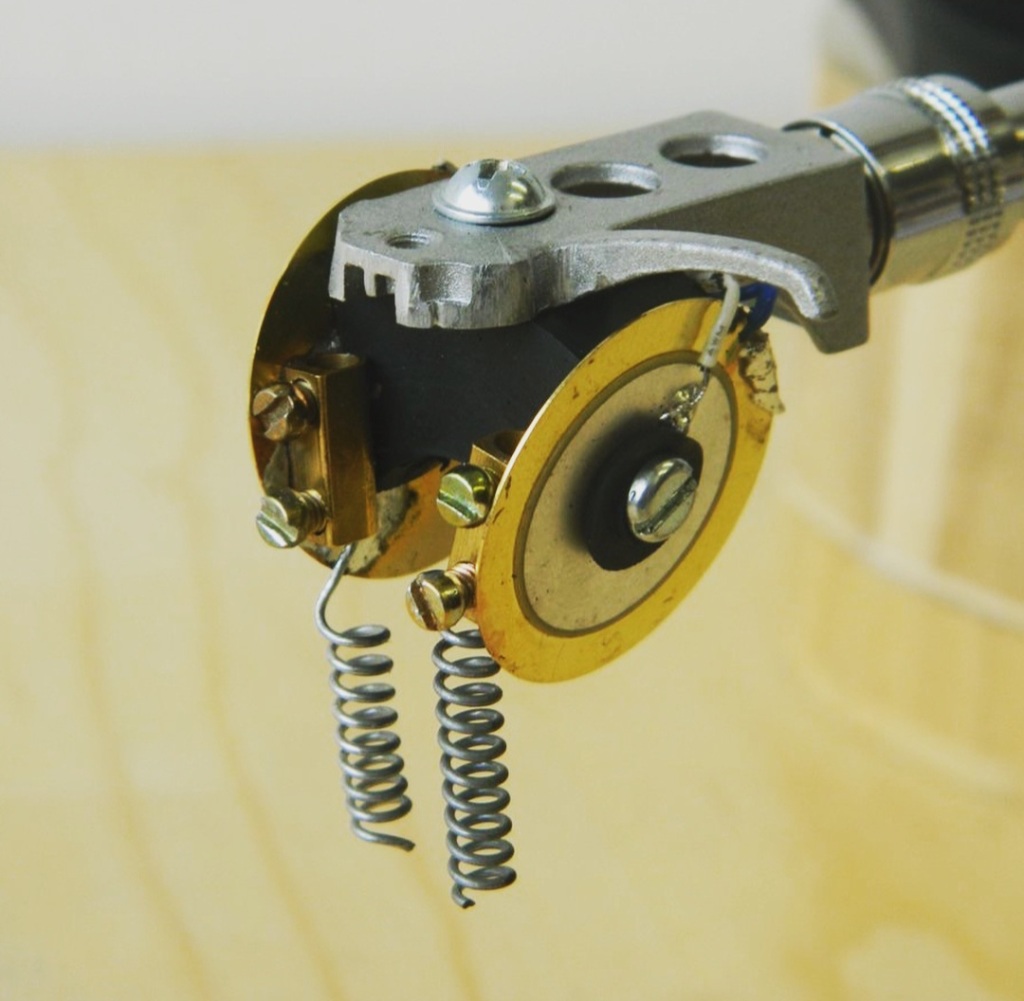

My own solution to playing mangled and abrasive records has been to use contact mics attached to a headshell, with screw mounts for different materials. There’s a similarity with gramophone needle attachments, which has reminded me that for acoustic shellac record players, alternative materials could be used to change the tone and volume of the playback. Steel gramophone needles are available in different loudnesses (presumably relating to the stiffness of the material) and sometimes bamboo needles were used for quieter playback. With my own headshell I’ve generally used cocktail sticks, kebab skewers, wire, springs, and plastic strimmer-blade line.

Most recently I wanted to play back a ‘tone’ record with lots of raised stickers on it, so didn’t want something that would damage the disk – fishing line proved very effective and also solved the difficult issue of making both sides of the stylus the exact same length to make contact with the record at the same time.

There’s lots more to say about alternative styluses, so this might be the first in a series of posts. And that’s before considering alternatives to turntables, alternatives to records, and other ways to read inscriptions by tracing a line.

Broken vinyl, record crackle and turntable contraptions in films and TV

Record players and other audio technology often crop up in feature films. My favourite examples are those when they’re essential to the plot. Like the secretly-taped confession at the end of Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil – a small portable tape recorder being somewhat of a rarity in 1958. Or the lathe cutting / record skipping plotline in Graham Greene’s Brighton Rock (different in the book and the film), written when recording your voice to disk was a novelty accessible on the pier for a few pence.

One example I found particularly intriguing recently was watching It’s A Wonderful Life over Christmas. Somehow I’d never got round to watching it before. In a scene towards the end, the lead couple set up a romantic scene in a derelict house with no electricity: a portable wind- up gramophone is used to turn a chicken on a spit in front of a wood fire. As someone so invested in extending the mechanical capacity of turntables through silly mechanisms I nearly jumped out of my seat. There’s a nice record-smashing scene earlier in the film too. I’ve had a half-hearted idea of documenting such instances for a while, not for any specific research purpose but more as a fun side project. The first instance of this sort that set off the idea was a scene in the 1955 film noir Kiss Me Deadly. In an act of bullying coercion, a copy of a Caruso shellac record is snapped in two. “That’s a collector’s item,” the villain states before breaking it. I mentioned these both on Mastodon in December and was helpfully pointed to this lovely web1.0 page, Phonographs in the Movies: Movies with phonograph scenes and machines. As is often the case on the internet, someone else got there first – their list doesn’t include the Caruso snap though. I never got round to such a formal and organised list, but might highlight a few examples on here as and when they come up.

I don’t go to the cinema particularly often but both of the most recent films I’ve seen have had very minor turntable errors, which I don’t think most people would notice, but I couldn’t help but pick up on. I’m not relating these here in a smugfaced ‘continuity spotter’ mode, more to highlight instances of old technology used as a signifier without the filmmakers minding too much whether they were using them properly – I think it’s quite an interesting phenomenon. (One of my favourite vintage audio gear youtubers Techmoan mentions some examples in a recent video too) Getting it Back: The Story of Cymande was a brilliant portrait of the black British funk band that were shunned at home, broke big in the US, were forgotten for years before being rediscovered through play at early New York loft parties and copious sampling on various hip-hop tracks. I genuinely enjoyed the film, but the b-roll footage of a close-up cheapo Crosley turntable used as an apparent zoom shot of someone playing a record on a 1210 irked me. I also finally got round to seeing Openheimer this week. Early on in the film is a closeup of a gramophone platter in action – which is spinning in the wrong direction. I wondered whether there was some allusion to turning back time (putting the genie back in the bottle?) but it didn’t seem a deliberate move in context with the rest of the film.

David Lynch makes use of vinyl several times in Twin Peaks. Audrey Horne dancing to the jukebox in the Double R Diner. The repeating record in Jacques Renault’s cabin in the woods, “where there’s always music in the air.” And the awful scene in the Palmer house where Leyland attacks Maddie – soundtracked by the runout groove of the record. Another subcategory of the broader ‘turntables on the screen’ umbrella is the use of record crackle as sinister sound effect. Often signifying the inevitable, the relentless advancing of the timeline to an inevitable conclusion, we know it’s unstoppable. It’s like a ticking clock, an endless countdown and a repeating cycle. Bjork’s Scatterheart from the soundtrack to Dancer in the Dark follows in the aftermath of another upsetting and violent scene, with record crackle underpinning the tragic song as the rhythm.

I’ve come to the end of the examples I had listed now, but don’t really want to end the post on such a miserable note. Perhaps also worth mentioning the various physical media artefacts represented in Minecraft. ‘Music discs’ look a lot like vinyl records, and are playable in craftable jukeboxes. The records are usually found in loot chests in various structures out in the world. Most are whole discs but there’s a broken one to collect too. The introduction of the Deep Dark biome in Minecraft 1.19 was particularly of interest to me: shards of broken records could be uncovered from beneath the earth, and pieced together again to form a unique, playable music disc. As someone who did basically the same thing for an artist residency in 2010 – excavating broken shellac pieces from an industrial site and setting them back together into a new record – I was over the moon.

Studio Visit: Furrowed Sound’s live vinyl tattooing

The world of turntable experimenters isn’t particularly large, and we tend to gravitate towards one another eventually. I came across Furrowed Sound, aka Dylan Beattie, via instagram fairly recently, and it turned out we had some mutual connections already. In fact, my extended turntable collaborator DJ Food by chance met Dylan through Ebay, and another friend Tom Bench had recently booked him for the Flim Flam night (which me and Sascha had performed at in late 2022). I appreciate these kinds of connections, an entangled web of technology, gigs and shared interests.

Furrowed Sound is a project which uses lathe cutting – the direct, real-time inscription of sound onto a disk – as a live performance practice. In effect, Dylan can sample live to vinyl, create physical loops on the fly, manipulate the sound by hand in the moment, and change and effect the playback during performance. The practice combines machine precision with human inaccuracy to create abundant opportunities for indeterminate outcomes.

Lathe cutting as creative practice has several precedents. Patrick Feaster’s essay on the often overlooked earliest sound recording experiments, “A Compass of Extraordinary Range”: The Forgotten Origins of Phonomanipulation, describes overcutting of grooves in Edison cylinders amongst other novel uses of the machines. Christian Marclay’s collaboration with Flo Kaufmann, Tabula Rasa, uses a back-and-forth exchange, with Marclay creating sound for Kaufmann to cut, which Marclay then plays back for further iterations. James Kelly’s thesis explored the lathe as a musical instrument, documenting and archiving examples of creative lathe-cuts, and creating new vinyl artefacts with which to record new compositions. Where Furrowed Sound differs is the live cutting and playback of records on a single machine, by the same performer: live sampling and loop creation with a very physical media.

Like me, Dylan is currently in the process of completing a practice-research PhD. He was kind enough to show me his setup and demonstrate the process, and even let me have a go at cutting some sound myself.

The image shows the setup in action. A very stable platter, itself from a professional record lathe, is turned by an ancillary motor via a rubber belt. The driving motor is a stepper motor from an old printer, controlled with an arduino – this allows for preset speeds to be accessed quickly as well as manual control of pitch shifting. The deck has two tone arms with three headshells: one stereo and one double-mono, based on the The Rake Double Needle by Randal Sanden Jr (as used by Maria Chavez). As the grooves cut to the disks are rarely a regular spiral, the tone arms can be held in position with threads attached to ‘helping hands’ posable arms – in this way they can be forced to stay playing a specific part of the record, whilst also having freedom to jump tracks due to the looseness of the thread. Finally the ‘tattoo gun’, shown being hand-held by Dylan, which is the tracking arm from a hard drive, fed an amplified audio signal. I’m describing the setup in very broad strokes here. This is an intricate and carefully developed project and requires an attention to detail and technical rigour I’m quite astounded by. Cables are balanced, various failsafe measures are in place to mitigate voltage spikes from mechanical pushback of the drivers, vibration is dampened in various ways.

Recently Dylan has collaborated in live settings with a cellist and trumpet player, and a live-looping vocalist. He also plays solo, using unfiltered tone generators and speech as inputs to the inscription needle. Various options present themselves during live performance. It’s possible to start with a ‘blank groove’, a locked cycle with no vibrational grooves cut into it, then add snippets of sound into and across it. Otherwise, a longer spiral can be inscribed, which the tone arm/s will follow, and end in a looping locked groove. In practice it’s difficult to be precise enough to make a needle loop by hand, so there will often be multiple interlocking spirals, loops, and scribble across parts of the surface – here the indeterminacy comes into play, the playback needles sometimes skating, sometimes holding, jumping in and out of grooves. A sense of rhythm is inherent to the system, like with many looping setups. Dylan demonstrated his skill in writing beats in real time, creating some wonky hip-hop rhythms out of bursts of pink noise.

My own attempt at cutting to disk was somewhat less elegant. I began with all three playback needles in fixed positions close to the edge of the record. My aim was to add some short pulses of square wave tones, changing in pitch as I progressed, building up something like a random melody. In practice it took much longer than I expected to locate the right position to etch – within a few cycles the pristine disk looked totally ruined with intersecting lines wildly battering the needles around. I did manage to cut some tones to the groove, and explored moving the cutter forwards-and-backwards with the rotation, creating unexpected results: the pitch gave a satisfying vibrato bend, as I’d been going for, but the stereo field was wildly modulated too. I find stereo encoding on vinyl fascinating, and it’s difficult to conceptualise even when you know the technicalities of how it woks. Here I think the changing angle of the cutter was causing variation across the speakers, and it added a wide and complex stereo oscillation which wasn’t present at all with the head in a fixed position.

I found the visit incredibly inspiring; from a technical perspective and through discussing some theory, but also down to Dylan’s enthusiasm for the project and generosity in sharing his ideas and process. Needless to say an exchange visit is on the cards, and we may even consider some collaboration in future. You can read more about Furrowed Sound on the website.

February’s radio show – tracks in focus

My radio show Fractal Meat on a Spongy Bone used to be fortnightly, live and in-person. Some guests either to play live or have a chat with, and a selection of tracks which I’d usually introduce and occasionally give a bit of info about. With experimental music it often helps to have a bit of context. Chaotic clattering is all well and good, but it can hold more intrigue if you know it’s a recording of a sound installation, or a location recording, or a live set or whatever. I switched to pre-recording a few years ago. For a while I kept the track intros in, but after a while that lapsed, in part because it doesn’t feel the same editing intros into a prerecording, as opposed to doing it all live. And to my ear always sounded a bit forced. This new blog feels like a nice platform to reintroduce some of that contextual information. The full tracklist for tonight’s show is on the show blog here, and you’ll be able to listen to the archive soon via this page. Below, some info about a few of the pieces in particular.

Renata Roman – Imensa

On their track from the Amazon Reimagined release, the Brazilian artist uses calm electronic tones and single piano notes alongside a soundbed of rainforest sounds: hissing insects, numerous birdcalls and other unidentifiable creatures. There’s a clear distinction between the played instruments and the field recordings. Whilst the latter have been edited and at points layered, they don’t appear to be processed much. The bandcamp page describes the project in a bit more detail: the sounds were recorded several years previously, between 2006 and 2011, in different areas of the Amazonian rainforest, and by several different people. I find this kind of time- and space-dilation appealing, bringing together potentially disparate sources into one imaginary soundscape. Steve Roden has used the term ‘possible landscape’ to describe his compositions1, which feels appropriate here. It’s a speculative soundscape, perhaps a snapshot of something that never really existed, which feels tragic with the knowledge of current and ongoing deforrestation.

Minimal Tears – Passing Back Into Light

Nadine Smith’s recent article about the changing way the major label music industry has embraced sampling gave me food for thought on the extent to which sampling as a process can be considered subversive. Most electronic musicians I know wouldn’t generally seek clearance for samples – the turnover is so low that most releases are likely to go under the radar, and in a scene where almost every break, synth sound or drum machine voice is already familiar, and part of what characterises certain genres, sampling feels like the raw material that makes up most of the music anyway. If sampling as appropriation without permission isn’t the straightforwardly political act it once was, perhaps sampling can work to build scenes and strengthen communities.

Maya Bouldry-Morrison (aka Octo Octa)’s Minimal Tears project is refreshing as it actively invites remixing, sampling and reuse – with explicit permission. The front page states clearly: ‘There is no copyright on this audio. Every part of it can be taken, used, edited, released, etc all without credit!’ In fact the release is under the CC0 Creative Commons licence, meaning the work is effectively in the public domain. There are complete tracks, their stems, and a collection of free samples to use too. The tunes are varied in genre, including synth-based ambient music, deep house and some with an electro feel. I chose one of the more abstract pieces for the radio show as it fit better with the rest of the stuff I wanted to include. The project continues to the positive and encouraging work both Maya and her partner Eris Drew do through their label T4T LUV NRG – check the main page for free pdfs of DJ tips, a guide to setting up a home studio, and a downloadable zine on grooveboxes.

Shirley Pegna, Emma Welton, Paul Whitty – Double-bass with Vibrating Soil

This kind of ‘does what it says on the tin’ track title is often my favourite kind of thing to include in the radio mixes. It’s a short track in comparison to the other pieces on the release, which feel more like straight up field recordings. On listening through, it’s still not entirely clear how the soil was deployed, or indeed whether there is a double bass involved at all – the liner notes on the bandcamp page list the instrumentation used as violin, field recording, objects, glass, and transducers. The title, and the release’s cover image, suggest to me a playful exploration of sound, literally out in the field.

Stephan von Huene – Totem Tone #4

Pipe organs are fascinating machines. I was lucky enough this weekend to witness a brilliant rendition of some baroque pieces on the free-to-use pipe organ at London Bridge station. Part of the joy for me is the deep, rich sub bass they can generate – I often daydream about how awe inspiring it would have been to hear such a thing hundreds of years ago, way before electronic sound reproduction.

Stephan von Huhne’s Totum Tones sculptures were built between 1969 and 1970. Each consists of a number of large, square-section organ pipes on a plinth containing an air supply and control mechanism. This recording of “Totem Tone #4”, from a 1975 LP, was made at the Vancouver Art Gallery – judging from the images on the sleeve, a large white cube space. The music itself has a lot of character. The tempo varies and the rhythm patterns don’t feel robotic, almost as though the pipes are being worked by a human player. Dispute the information on the artist’s website, including some closer images and (slightly vague) descriptions of the mechanisms, I couldn’t work out exactly what’s happening. There are sections where the pipes begin to overblow, and what sound like beat-notes at times – again, characteristics which I’d associate with nuanced human playing rather than programmed control.

Michael Ridge – Mutant Flexi Cut-Up #2

Another self-descriptive piece, here Michael uses cutup felix-disks recorded to dictaphone cassettes, for double grunge noisy clatter. We’ve been in touch online for a few years, having some crossover in our turntable practice, and general lo-fi / hardware hacking stuff. I’m hoping we can meet in person at the weekend, as he’s due to play a show at Hundred Years Gallery (London) on Saturday evening. [Edit – no he’s not! turns out the gig is actually 24th March, not February. Hopefully can catch him next time.] One of the other things I miss now I’m pre-recording the radio show is to be able to preview and promote gigs and things happening locally. This show is organised by Mouth In Foot, who had asked if I’d give the gig a mention. I can’t find it on the venue website yet but will be heading down – a lineup of turntablists and tape manglers, including Michael Ridge and Eggblood.

Brötzmann / Bennink – Schwarzwaldfahrt Nr. 1

A different approach to combining live instrumentation and environmental sound, here Peter Brötzmann and Han Bennink duel on wind instruments in the Black Forest. This release has been on my mind recently as I was co-writing a paper about the way improvisation works when using a system with unpredictable elements. Considering the environment itself within the ‘performance ecosystem’2 as a contributing factor not just to the sounds captured on the recording but also as something the players might respond to or be influenced by. Here the saxophonists appear to be moving around the woods, their cries becoming increasingly birdlike, fading with distance and giving way to more delicate birdsong from the local species. I’ve been lucky enough to visit the Black Forest several times, on tour and an artist residency, in Sankt Georgen im Schwarzwald, which is also home to the German national phonography museum. It’s quite uncanny how evocative the sonic space feels listening to these recordings from nearly fifty years ago – the particular reverberance that seems coloured by the canopy and the floor thick with pine needles.

Chloë Sobek – Thrall

Michael-Jon Mizra – Framework

One of my favourite recent compilations, LOLTRAX001, I’ve played tracks from it in the last few episodes – this tape keeps on giving. Diverse approaches to computer music with live coding featuring heavily. Both of these pieces include drones and glitchy click-crackles, both feel equally futuristic and sort of biological.

As this selection perhaps illustrates, I don’t generally program the radio show by theme or genre, but there do tend to be threads that connect many of the tracks. I enjoy including audio that might not otherwise get much airplay, or listening time, so particularly the sound installations. I enjoy playing very recent stuff and try to feature new releases amongst older pieces and material by more established artists. Hopefully it’s of interest to read a bit more about some of the work.3

- Steve Roden ‘what are you doing with your music?’ in Brian Marley & Mark Wastell (editors): Blocks of consciousness and the unbroken continuum, 2005. ↩︎

- Simon Waters – ‘Performance ecosystems: ecological approaches to musical interaction’ in EMS: Electroacoustic Music Studies Network (2007): 1-20. ↩︎

- I wasn’t planning to be rigorous about referencing etc on the blog, as it’s here mainly for me to practice at writing and hopefully get quicker and more confident with it. But it feels necessary when mentioning specific concepts like these, and again it might come in useful to someone reading. ↩︎

How a venue sustains communities

Living in London sometimes I feel spoilt by the amount of music, art and performance on offer. It’s often more a case of choosing what you have to miss out on than struggling to find good things to see. There are loads of venues that support experimental and electronic music of different shapes and sizes, from international touring artists to local free improv linchpins to wild DIY noise. One venue hosted all of the above, and has been central to various scenes for a decade. But sadly, Iklectik Art Lab, at its home near Waterloo anyway, closed its doors for the last time at the start of 2024. The former hospital building on the edge of parkland has gone the way of many before it and been sold off for development. Despite a well supported petition and even requests to the Tory cabinet, which at one stage seemed promising, the site owners refused to renew any of the businesses’ leases, and the land will now be unoccupied and unused until development begins.

Undaunted, Isa and Edouard have big plans to set up a new Art Lab, and are crowdfunding for their first six months’ rent on a new space, plus soundproofing and other setup costs. If you can spare a bit of money, even a few pounds, the crowdfunder page is here. The new project sounds really ambitious and exciting, so I hope they can make their (equally ambitious) target – they’re currently ⅔ of the way there which is a good sign.

Iklectik really felt like a central hub for various interconnected groups or scenes of experimental music. Longstanding events, sometimes based around a concept, other times around a group of people, which found a home at the venue and built a community around them. As well as advertising the crowdfunder I wanted to talk a bit about some of my favourites.

Apologies in Advance is Tom White’s event series, with the explicit aim to give artists a platform to try new ideas, take risks and push their work. Although some of the shows happened at other venues, Iklectik felt like the series’ home base. I took students from my old Experimental Sound Art evening class to one edition in 2018, including many people who had never been to any sort of experimental music gig before. A huge highlight was Lia Mazzari & Sholto Dolbie’s set which took place outside the building, the artists behind a fence just inside the neighbouring park. Sholto moved air pumps around blowing reed pipes, whilst Lia made sharp cracks with a whip, the sounds ricocheting off the neighbouring buildings. With a minimal turntable set from Hannah Dargavel-Leafe, featuring field recordings from aboard a ship from her Fore Main Mizzen release, and a chaotic, noisy collage-improv set from I DM THEFT ABLE, stopping off on an international tour, it’s fair to say that minds were blown. The students got loads from the event and it really showed in the work they made later in the course. Seeing artists taking risks and exploring new ideas in a positive and receptive setting really set the students up to confidently push themselves too.

Boundary Condition is an ambitious audiovisual event ran by Alaa Yussry, aka Cerpintxt. With some events running all day, the lineups were often huge, ranging from film screenings and live soundtracks to improv sets, live electronics and dancefloor focused stuff. As such the event reflects Alaa’s own interests and approaches, and indeed she often performed at the night. Again, as a prolific promoter, she programmes shows at various other venues, but the large and bright projector with its full-wall resolution, plus the full surround soundsystem gave lots of options for AV works to be presented in a great context. An edition I attended in 2023 featured performances by nine artists including: the premiere of a film shot in remote settlements in Tajikistan by Carlos Casas, live soundtracked by Cerpintxt (who also did a completely different collaboration with pianist Rueben Sonnoli later); a chaotic improvising electronic quartet Infinite Monkeys, whose all-round-the-table setup felt like a surreal conference meeting; and Robin The Fog‘s live set as Howlround, coaxing drones, screams and throbbing bass rhythms from old BBC tape machines.

Hackoustic is a showcase of instrument makers, hardware hackers, installation artists and other musical experimenters, brought together by Tom Fox and Tim Yates. Another event series which very much feels like a community, it’s not unusual to see previous presenters amongst the audience. Hackoutik feels like the sort of event which has the capacity to facilitate real-world meeting of people from an otherwise fairly online scene. As a maker it can sometimes feel quite isolating putting together a project. The hours spent in the workshop are usually alone, compared to, say, a band working on new material. Using the instrument at a gig, or exhibiting an installation, or whatever, doesn’t always afford the opportunity to share the thinking behind the work and connect with people in that way. We’re all busy squirrelling away in our workshops and chatting online but rarely meet in person. I’ve been pleasantly surprised several times to see familiar faces at the events. Arlene Burnett came down from Birmingham to show her sound-generating plants modular system; Gordon Charlton presented his compositions based on sonifying various mathematical formulae. Both people I’ve encountered over the years but not been in regular contact with, lovely to see them again in London.

This post is getting somewhat long now so I’m not going to go into too much more. I wanted to talk about The Horse improvised music club, Robin’s annual Fog Fest, Club Integral, Exploding Cinema, Sonic Garden… the list goes on. Not to mention all the labels who launch releases at Iklectik, events by affiliated uni courses, one-off shows by promoters like Baba Yaga’s Hut, and all the in-house events too. On a personal level Iklectik has meant a great deal to me. In the spirit of the above nights I’ve tried loads of new ideas and debuted new projects at Iklectik, including:

— playing halflife with all the sounds replaced with rave samples (for Apologies in Advance) [video]

— turntable and electronics duo with Cath Roberts (for Overtones & Undertones) [video]

— modified turntable duel with DJ Food (for Fog Fest) [video]

And loads more.

It’s really sad, then, that Iklectik has closed its doors for good at the Waterloo space. But hopefully Isa and Eduard can move on to bigger and better things and continue to maintain the various communities they’ve worked so hard for. If you can, please contribute a few quid to their crowdfund.

Quietly launching

Over the last couple of years I’ve made various attempts at reducing my tendency towards doomscrolling. I left both facebook and twitter in part due to the negative impact it had on my wellbeing, and the inability to mitigate the constant feed of frustrating and upsetting political articles. At one point I switched to reading actual news sites instead, without feeling any better.

Looking for something less miserable to read in moments of downtime I initially tried the reddit app and a joined a few subreddits related to my interests – starting quite broadly with music, climbing, specific TV programmes and computer games, and fifth edition Dungeons & Dragons. I quickly tired of the (often quite depressing) chat on the techno and electronic music production boards. Outside of my old twitter echochamber – musicians and producers I liked and mostly knew, quite a diverse bunch and generally pretty right on – the wider electronic music community on reddit was blokey, entitled and often argumentative. Bouldering subreddits were usually too technical and dry. There are only so many Half-Life memes I want to read on a daily basis. So I eventually gravitated towards the D&D boards, finally narrowing down to one of the DM forums. A good balance of in-depth answers to obscure questions about lore; agony aunt style threads on problem players and how to deal with out-of-game social interactions; and useful tips for running a game. As with many things on the internet nowadays, and this may be a topic I return to, enshittificaion reared its ugly head. Changes to the back end of reddit meant moderators’ jobs would become exponentially more time consuming, and various boards were set to private, essentially going on strike to protest the profit-driven changes negatively affecting the communities.

I spent some time working though daily crosswords, and had a bit of a self improvement drive on duolingo, before deciding to try an older approach to sourcing bite-sized reading material, the RSS feed. I use an Android app called Feeder which is simple and handy, allowing copy-pasting of a URL to look up a feed to add. It took me a while to find blogs I wanted to follow – and I had lots of help from folks on Mastodon with some great recommendations. I’m finally at the stage I have an app I can open to read stuff I’m interested in, that’s not trying to sell me anything or start an argument. Reading blogs about people’s niche interests is incredibly satisfying. This morning in the dentist’s waiting room I learned all about the workings of a mechanical aircraft computer. The blogosphere feels like a wholesome space to visit in periods of downtime, to me. I find people’s enthusiastic posts encouraging. I like having a feed of bits of info about new weird music releases or new synth modules and software.

I’m currently in a position where I’m doing a lot more writing than I’ve probably ever done. I’m in the second year of a PhD, which is a practice-research project looking at the affordances of my extended turntable system. There’s lots of practical work, spending time building new interfaces and soundsources, making and recording music, collaborating with other artists, and performing live. But there’s a lot of writing too. I’m keeping notes relating to most of my activities in regular reflective journals. Writing notes and ideas as they occur to me. Paraphrasing other writers’ concepts to help me make sense of them. Plus the various administrative documents, literature reviews and reports that the study requires. So far in 2024 I feel as though I’ve spent most of my time writing, having finished co-writing an article for a journal, completed a paper for a conference and written another abstract. The process is new to me, and I’ve found it quite difficult – in part due to feeling quite unconfident, due to my inexperience.

So here we are, at my decision to begin blogging. I’m posting for these reasons: to contribute something back to the community that is the blogosphere, and to give myself more practice writing and putting it out there. I’ve been inspired by recent posts on blissblog and disquiet and it feels like now is as good a time as any.

Previously I used the feed on my website for news updates, posting for every single gig, release, radio broadcast and mor. There were nearly 500 posts on here, mostly of a couple of lines of info and a link. I stopped doing that during the Covid pandemic, and in setting up this blog I’ve got rid of those articles. The past posts I have kept are ones where I’ve written a bit more, both selections of music for quest mixes: a podcast about turntablism and a radio show about mechanical music. Going forward I’m aiming to post a couple of times a week with thoughts related to sound and music, things I’m working on in the studio, recommendations for books, podcasts and music and whatever else might be seem relevant. It’s likely this blog will take a while to settle into its groove, but I’m looking forward to seeing where it goes.